Progressive or Regressive?

Tax fairness usually addresses whether tax burdens are progressive or regressive. With a progressive tax, the share of one’s income paid out as taxes rises as income rises, which is considered fair. With a regressive tax, the tax burden falls as income rises, which is considered unfair.

Generally, property tax is seen as progressive because high-income earners are more likely to own more expensive property and pay higher property taxes. Low-income earners are more likely to be renters, and depending on the strength of the rental market, landlords may not be able to pass through some of the property tax to their renters. Many cities and towns also have property tax exemptions for low-income households. Sales tax is thought to be the most regressive because not only does it tax the first dollar of spending, but it also burdens low-income earners disproportionally, who spend most of their income on basic needs. Income tax is progressive to the degree that the marginal tax rate rises with income, and the first dollars of income are tax-exempt.

Free-Ridership

Tax fairness also relates to who pays the taxes and who reaps the benefits of the services that the taxes fund. An imbalance between those who pay and those who benefit results in what is known as “free-ridership” or “free-riding.” Typically, this is a local taxation issue and is not identical to the concepts of redistribution or regressivity.

A city or town reliant on property taxes may have a free-ridership problem. Consider a city that has big box stores. These stores attract residents from surrounding communities who bring cars, which cause road wear and tear, as well as the need for traffic control, street lighting, garbage collection, police and ambulances, and other city services. But that city may be funded solely by the property taxes of the city’s residents. Although commercial establishments also pay property taxes, and their customers pay prices that capture the cost of taxation in turn, those taxes are not well aligned with the utilization of city-provided services. Further, not only do residents of larger cities and towns bear the tax burden, but they also absorb many negative externalities, such as noise pollution and reduced public safety from the transient population. Is it fair that residents of these cities pay for services used by “out-of-towners” who do not contribute to the cost?

Tax Burden and Population

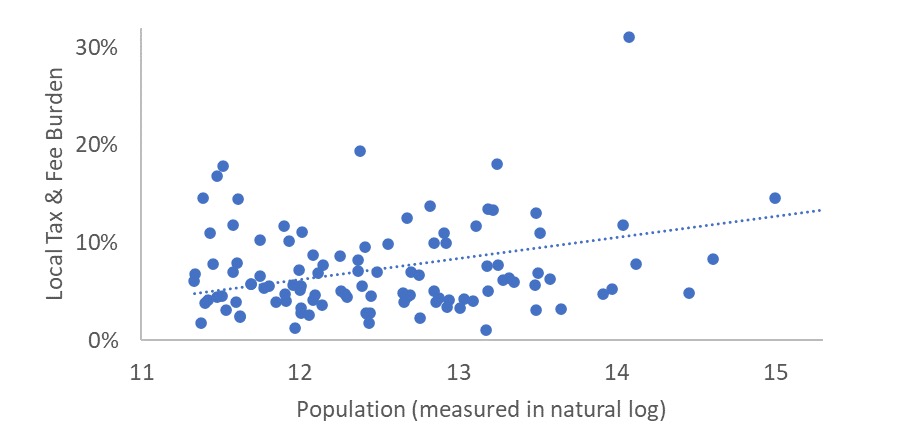

Free-ridership may also be regressive. Not only do larger cities have more free-riders, but generally, tax burdens are also higher in larger cities. Using a broad sample of more than 100 cities with populations greater than 100,000, the correlation between the local tax burden, which is local taxes as a percent of income, and population size was observed to be 58%. So, unless there is a corrective cash redistribution from state funds to the local level, larger cities will continue to experience unfairness from free-ridership and potentially additional unfairness should their residents have fewer economic resources relative to out-of-towners.

Tax Burden and Population

Correlation coefficient = 58%.

Source: Pality.

Tax-Exempt Organizations

Tax-exempt property associated with non-profit institutions further compromises tax fairness. As an example, hospitals and universities, which are tax-exempt, invite free-ridership as they draw residents to utilize their services from well beyond the reach of a city’s taxing arm. Even when states provide relief through payments-in-lieu-of-taxes, these transfers rarely make the cities and towns whole from the foregone revenue associated with tax-exempt property. Yet again, the city’s residents must cover both direct costs, such as more traffic control, as well as indirect costs, such as noise pollution and reduced public safety. On top of this, they are shouldering the direct and indirect costs with fewer tax resources.

Can tax fairness be restored in cities and towns experiencing free-ridership?

If a state provides direct transfers of revenue from state-levied income and sales taxes to cities and towns experiencing free-ridership, fairness can be restored. However, if the state levies new taxes to fund these transfers, unintended consequences may arise, such as economic distortions and tax avoidance schemes. Further, once a tax is established, it is difficult to remove or reduce it. Finally, even if it is neutralized at the onset with a lower local property tax, the overall tax burden may creep up over time.

Written by Joseph Cahill.

Copyright 2023 Pality.