What the general fund does not measure

The General Fund of a town, county, or state is often viewed as a measure of fiscal health. Is it positive or negative? Large or small? Growing or shrinking? The balance, size, and trend of the General Fund are all good statistics to examine, but when considered alone, the General Fund is not an adequate measure of a government’s fiscal health.

Liquidity

The General Fund reflects short-term liquidity. The General Fund balance is like your checking account balance. There may be cash in your account, but this says nothing about your net worth, which is calculated as your total assets minus your total liabilities. How much have you saved for your child’s college education or for your retirement, and do you have equity in your house? These are your assets. Do you have liabilities such as a mortgage, a car loan, or credit card debt? Many of us have experienced having money in our bank accounts despite having high credit card debt, minimal home equity, or insufficient savings for college or retirement.

Solvency

The General Fund does not answer the question, “How fiscally secure or solvent is my town, county, or state?” because the General Fund does not capture long-term liabilities. The questions that the General Fund answers are, “Can my government pay its bills that are coming due in the short term?” and “Is there cash for a ‘rainy day’?”

If a state or local government is not fiscally secure, it must raise taxes, cut spending, issue debt, reduce contributions to its retirement obligations, or some combination of these options. These decisions will directly affect many constituents, including taxpayers, employees, vendors, bondholders, and public sector retirees, both current and future.

Unrestricted Net Position and Solvency

If the question is, “Is your state or local government fiscally secure enough such that your taxes are less likely to be raised to amortize your government’s liabilities?”, the answer lies in the Unrestricted Net Position. The Unrestricted Net Position is a balance that reflects whether the government has sufficient assets to meet all liabilities without resorting to liquidating building and land assets or dipping into special-purpose funds.

The General Fund is not correlated with Solvency

Not only is the General Fund balance not an indicator of fiscal health, but it is also not positively correlated with the Unrestricted Net Position balance. In fact, the statistical correlation between these two balances is negative 29%.(1)

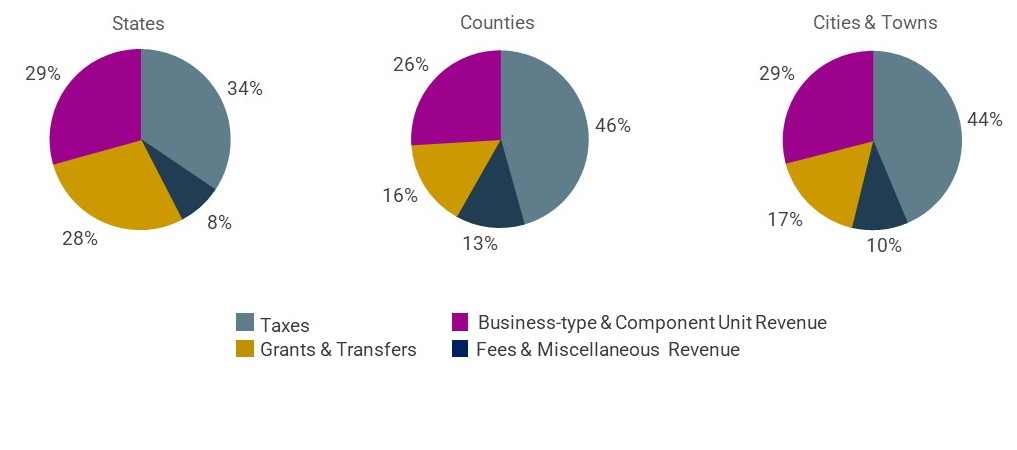

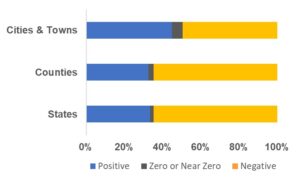

Just how fiscally secure are state and local governments? Only 33% of all states, 33% of sampled counties, and 45% of sampled towns (cities) have a positive Unrestricted Net Position. Sixty-five percent of states, 65% of sampled counties, and 50% of sampled towns (cities) have a negative Unrestricted Net Position. The remaining states, counties, and towns have an Unrestricted Net Position of zero or near zero.

Unrestricted Net Position of Cities & Towns, Counties, and States, FY 2021.

(1) Includes any government “rainy day fund” balance, which may be a distinct reporting category. If “rainy day funds” were excluded from the data used for the calculation, the statistical correlation would be more negative.

Source Pality.

Written by James Galasso.

Copyright 2023 Pality.